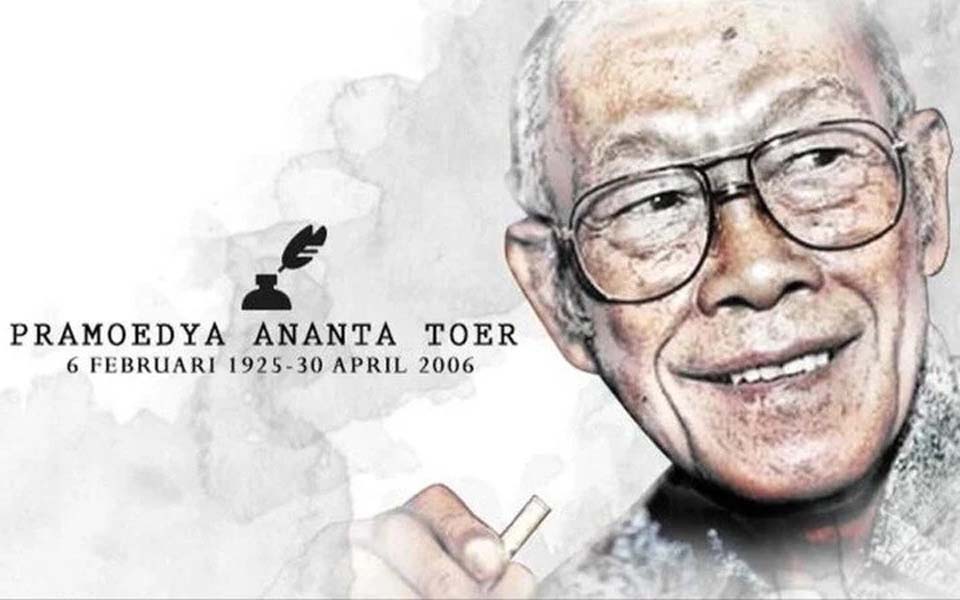

Hilmar Farid – History, literature, and imagination come together in the life and works of Pramoedya Ananta Toer. He not only wrote literature, but also explored history and used words to revive the past that was deliberately deleted.

In the Buru Tetralogy (Quartet) he processed the results of his historical research into four volumes of novels that not only aroused the collective memories of the nation, but also catapulted Indonesian literature onto the world stage.

For Pramoedya, history is the upstream reality – the raw materials that are the source of imagination. A writer, with the alchemy of words, he changes the upstream reality into the downstream reality – the literary work that tells the story of the past.

In this process, history is not only reconstructed, but is revived, forming an imagination in the minds of the reader, which ultimately helps determine the way people understand the nation and their identity.

Imagination in this case is not an empty or baseless fantasy, but a solid image about the origin and journey of a nation. If this image grows in collective consciousness, it can be a powerful force. During the Dutch colonial period, this kind of imagination encouraged people to fight and sacrifice for Indonesia's independence.

Rewriting the past

Pramoedya experienced firsthand the power of imagination when he joined the army to defend the Republic at the beginning of independence. He wrote a novel and short story to present this complex reality.

The revolution is not just to drive out the colonialists, but also about how violence can become a legacy that destroys if it is not balanced with moral awareness and clear goals.

During period of independence, he traced the origin of moral awareness and goals that shaped the independence movement. In his search, he met with Tirtoadhisoerjo – a thinker and activist, founder of the Medan Prijaji newspaper, as well as the pioneer of the Indonesian press. He wondered why this important figure was not much talked about and even seemed deliberately removed from history.

Through in-depth archive research, Pramoedya revealed how Dutch colonial power had removed Tirtoadhisoerjo from collective memory. He then used the same archives to write a series of articles that returned the figure into the history of the nation.

Pramoedya realised that history, if not remembered, will disappear – and a nation without historical awareness will be adrift without direction.

In this instance, Pramoedya is among the ranks of other anti-colonial writers, such as Chinua Achebe from Nigeria and Ngugi Wa Thiong'o from Kenya, who wrote history to build historical awareness as a catalyst for collective action.

With a strong historical awareness, a nation has an understanding of where it come from and where it has walked, creating history – an upstream reality – that is new. This is the real movement of civilisation.

However, these efforts foundered when geopolitical interests met with internal conflicts in the nation's body. Founding Indonesian President Sukarno and his anti-colonel nationalist project were destroyed.

History was rewritten, and figures like Tirtoadhisoerjo again disappeared from official record. Pramoedya himself was removed from public life. In October 1965 he was arrested and imprisoned without trial for 14 years, while his works were banned and removed from libraries.

After being released in 1979, he was prohibited from writing, teaching or working in fields related to the public. His name was even deleted from various official records, sometimes with absurd methods.

I remember in the mid-1990s, I found his name in the telephone book, not in the white page, but in the yellow pages, as Pramoedya Ananta Tour. Was it intentional? Who knows, but that was the fact of it.

Prison and imagination

The first years in prison on the isolated Buru Island were a heavy time for Pramoedya. To maintain the spirit of life, he began to tell stories to the other prisoners.

At night, after forced labour was over, he sat in the barracks, surrounded by those who wanted to listen to his story. He told the story of a tough woman who fought against colonial injustice – Nyai Ontosoroh – who would later become an important figure in his Buru Tetralogy novels.

In November 1973, Pramoedya was finally allowed to write. He had intended to continue his historical writing project that had been broken off, but had absolutely no access to archives or supporting documents. Some officials who met him promised to help, but from Jakarta came bad news: his library had been looted. Thousands of books, dozens of meters of archives, and important documents had been destroyed.

Under these limitations, he found another road. He rewrote the stories that he had only conveyed verbally to the prisoners on Buru Island. From there was born the legendary tetralogy.

Without research materials, he immediately worked on downstream reality – not to change history, but precisely to restore it. This is the power of literary works. Pramoedya knit the pieces of past into a living narrative. The reader does not just follow, but experiences the story.

We feel the inner struggle of the main protagonist Minke, we are amazed by Nyai Ontosoroh's courage in the colonial court – and all of this forms an awareness that this nation was born from a long struggle against injustice.

The story that was born from a prison then spread throughout Indonesia – and the world. His books have been translated into dozens of languages.

When they were banned by the government of former president Suharto, the books remained circulating, passing from hand to hand, read and discussed, while avoiding the sensors and repression. A movement was formed from this shared imagination, just as he wrote in the tetralogy. Downstream reality formed upstream reality.

Imagination and nationhood

Pramoedya's historical writing project was in line with the Trisakti (three principles) concept initiated by Sukarno: forming a sovereign nation in politics, economic self-sufficiency and cultural independence.

In his time, this idea was considered a threat by the global political powers which then worked on a campaign to get rid of Sukarno, along with dozens of other Asian, African and Latin American leaders who had the same orientation.

For Pramoedya, the solution to this situation is not to return to the past. For him, the past is also not something ideal. He criticised the Indonesian nationalist revolution, inequality during the Sukarno era, as well as discrimination against the Chinese community – a criticism which in the end led to him being imprisoned for a year.

However, all of these criticisms are not just a historical record, but must be the foundation for the new national imagination, in order to form a fairer and more inclusive upstream reality.

Today, the body of Pramoedya's historical novels is no longer just a literary work. They have become part of the history they describe. The imagination formed in the mind of the reader continues to support the struggle to form a new upstream reality – a struggle that is not yet finished.

- Hilmar Farid is a cultural observer and historian, a former People's Democratic Party (PRD) activist and the former Director-General for Culture at the Ministry of Education and Culture.

[Translated by James Balowski. The original title of the article was "Pramoedya dan Kekuatan Imajinasi".]

Source: https://www.kompas.id/artikel/pramoedya-dan-kekuatan-imajinasi