Toto Suryaningtyas – Efforts by certain politicians to pull the military back into the political arena has tended to receive little public agreement. This disagreement however has in fact been expressed at time when the public’s sense of satisfaction with the performance of the Indonesian military (TNI) has improved.

Viewing the character of the military as an organisation that is professional and safeguards the ordinary people is one thing, but involving the military in the domain of political power is a different matter. These two view points, which post the abolition of ABRI’s (the Armed Forces of the Republic of Indonesia, the TNI’s former name) dual social and political function, which has further separated the military from civil power, are still held quite strongly by the public.

The results of a Kompas survey indicate that the proportion of the public that disagrees with the military returning to politics is quite large, as many as 65.5 percent of respondents, while only 29.7 percent agree. This proportion does not change significantly with regard to giving military personnel the right to vote with as many as 61.1 percent opposing this while only 35.7 percent agree.

If explored in more detail, the difference in respondents’ social backgrounds do not appear to greatly influence these different assessments of the TNI’s right to vote. Nevertheless, the indication is that the higher the level of respondents’ education, the larger the proportion of respondents that disagree with the military having a practical political role or giving voting rights to the military.

On the other hand however, the results of several surveys indicate that the public’s tendency to oppose the entry of the military into the political domain appears to be quite dynamic in character, changing over time along with the military’s behaviour and the country’s political situation at a given time. In addition to this, the public’s opposition to the inclusion of the military in the political domain itself tends also to depend on situation and whether it is individual officers or the military as an institution that enters the civil political domain.

In a situation of crisis for example, when the security aspect becomes a crucial issue, such as the conflict that occurred as a result of the South Sulawesi Gubernatorial election or other horizontal conflicts (Ambon, Poso and Aceh), military leadership is more acceptable than civilian. A January 2008 survey indicated that the majority of respondents (71.7 percent) agreed that the regional head of area hit by conflict should be a military officer. One of the main effects hoped for by the public from the placement of a military officer in a conflict area is the restoration of security in a region.

Conversely, the majority of respondents are not convinced that the placement of a military officer will bring with it opportunities for improvements, particularly economic improvements, in regions that are not effected by conflict. In peaceful or normal situations, the public prefers to elect civilian bureaucrats rather than military officers. According the survey conducted in early 2008, more than half of the respondents (53.6 percent) elected civilian bureaucrats compared with one-third of respondents (37.7 percent) that elected officials from the military.

The military’s political role in Indonesia’s political history is often stated as being a call to respond to the political conditions that exist during a given period. It began with those military circles that were anxiously looking at the atmosphere of the 1950s parliamentary governments, which was unstable and ridden with infighting. The political parties and politicians were unable to prevent fights between each other and taking turns at bringing the government down.

In this situation, Armed Forces Chief General Nasution raised the concept of a “middle road” with the TNI taking an active role in helping the nation. The TNI would avoid both the political style of the military in Latin America, which became involved directly as an active political force as well as the West European style where the military acted passively to maintain the status quo, simply representing a “tool of power” for the government in power. Clearly, the TNI would not act politically by launching a coup, but it would also not simply become a spectator in the political arena.

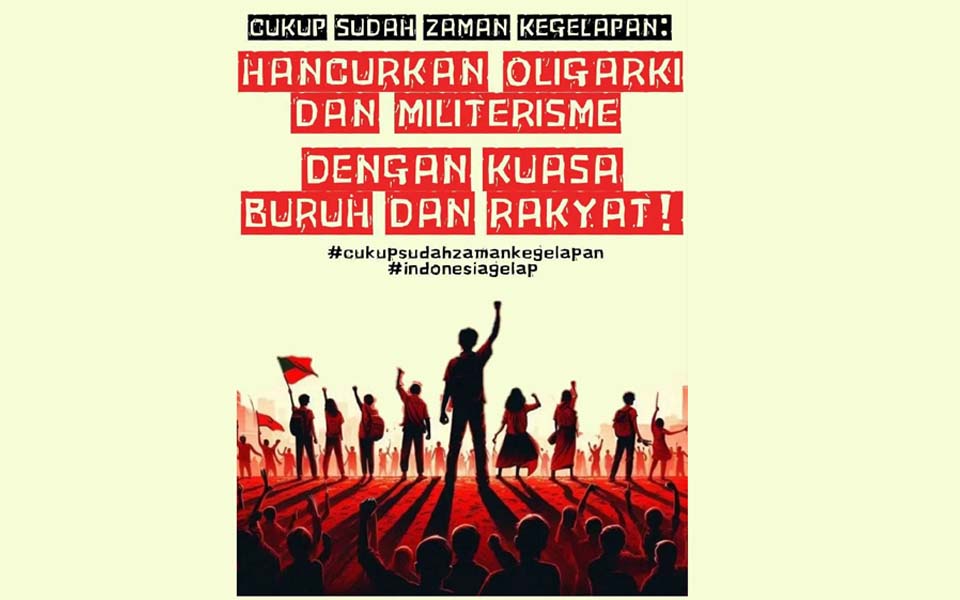

It was this concept that in coming days became the precursor to ABRI’s dual function. Later, as a consequence of the military as an institution being ensnared as a tool of power by Suharto’s New Order regime, the excesses from the military’s political role that were initially “well” intended, slowly but surely became a parasite that undermined the life of the nation and state. ABRI’s dual function became a symbol of the repression of authoritarian power that perpetuated its power through political power and military arms.

President Suharto’s resignation and the collapse of the New Order brought about fundamental changes to the military’s position in the political structure of the state. After the TNI was separated from the National Police through People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) Decree Number VI/MPR/2000, the paradigm of the TNI’s role as the guardian of state security and its separation from sociopolitical affairs became more clear cut.

The position and function of the TNI as an institution was further regulated through MPR Decree Number VII/MPR/2000, which regulated the TNI’s neutral position in the political life of the state. Finally, through legislation, particularly Law Number 34/2004 on the TNI, the stipulation that TNI would not have a political role was spelled out again more clearly. And it was not just that the military were not permitted to become involved in practical politics or become members of political parties (Article 39), but it also affirmed the military’s respect for and acknowledgement of democracy, human rights, the laws of the state and even civil supremacy (Article 2).

On the one hand, there appeared to be a clear desire on the part of legislators and reformist circles within the TNI to turn the Indonesian military into a professional military force that stands above all groups and factions in the paradigm of safeguarding the country’s interests, the final bastion of the state. Within such a format, the dynamics and chessboard of domestic politics was surrendered to civil groups.

Unfortunately, the enticements of political power, just as they were in the past, are not something easily abandoned. One piece of evidence for this is the TNI’s involvement as an institution or individual members in many business interests. Likewise the involvement of retired TNI officers – although they are permitted under law – in earlier rounds of regional elections. Out of the 179 regional elections held in 2005-2006, more than 3.4 percent of candidates who won had a military background. This figure is far greater if it includes a calculation of the candidates that registered. It is estimated that this proportion will grow in the final round of regional elections this year.

Increasing appreciation

Concerns about the military’s return to dominating the arena of civil power, just as occurred in the past, are the main reason for the public’s concerns about the military. It appears that for the public it is not very important to distinguish whether a person is an active or retired member of the TNI. The experience of past human right violations, enforced ideological indoctrination and the corrupt control of the administrative structure, carries too much of a risk to allow it to reoccur.

In a succession of surveys on the TNI over the last four years, the indecisive picture given with regard to the return of military officers into the civil political chessboard indicates a relatively fixed pattern: with respondents on the one hand rejecting this, but able to accept certain aspects of it. The results of a survey in September 2008 indicated that 69.6 percent of respondents are of the view that over the 10 years of reformasi or political reform (since 1998) the TNI has not yet been able to keep its promise to reform itself and has tended to return to politics.

A note of concern over a return to military domination was articulated by more than half of respondents (in the latest survey the proportion was greater again). On the other hand, a survey in January 2009 found that the public tended to strongly agree with certain aspects of military leadership: discipline, competence, obedience, good organisation, in plunging into activity in the political parties or parliament in the midst of the confusing and disturbing behaviour of civilian politicians.

Uniquely, some of these concerns and the conditional acceptance of the TNI’s role in politics have occurred in relatively peaceful situations, where both external as well as horizontal conflicts have been relatively quiescent. Likewise also when there have been few upheavals within the TNI itself and it has been relatively free from frictions internally or with other institutions. Under such a situation, the public’s assessment of the TNI tends towards a normative institutional function with regard to the state.

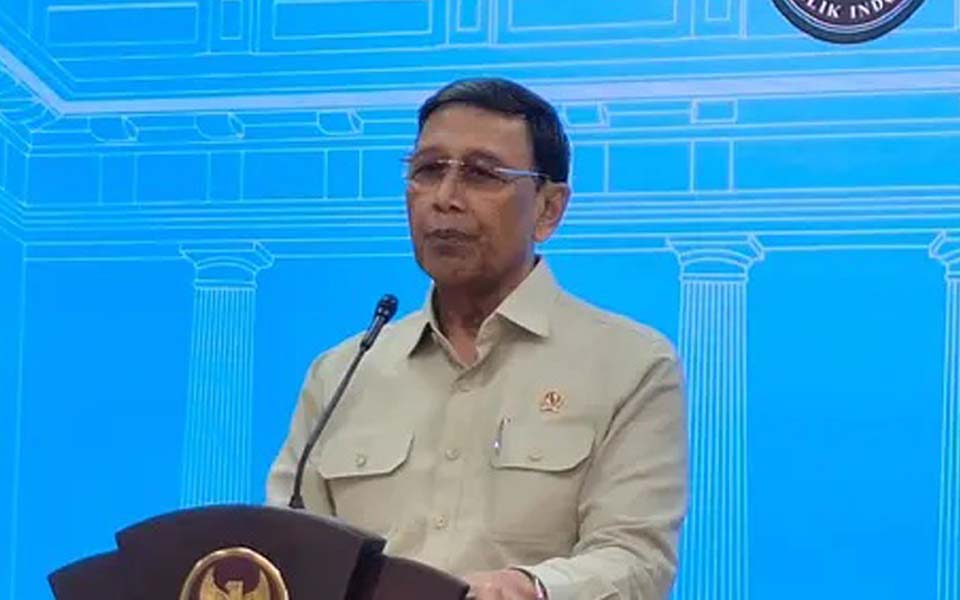

It is because of this therefore that is not strange that in the midst of the disagreements in the discourse over the TNI’s political rights, the public’s appreciation of the behaviour and image of the TNI as an institution has in fact risen sharply. Based on Kompas’ data, the TNI’s image in the eyes of the public has reached the highest level of appreciation since 1998, as high as 71.5 percent. Not only that, from the aspect of the general level of satisfaction with the TNI’s performance, over the last three years this has risen by up to one point per year (this week reaching 73.3 percent of respondents who said they were satisfied).

In terms of political momentum, the highest point of the public’s appreciation of the military coincided with the abolition of the TNI’s political role in practical politics, the end of its representation in the parliament and MPR, and the increasing clarity of its role as a profession military. Without downplaying the need to pay attention to improving the welfare of TNI members and eradicating corruption, collusion and nepotism within the TNI as an institution, it is fitting to question whether there is a need to again tinker around with the TNI’s political rights at a time when it has achieved such appreciation in the public’s eye. (Kompas Research and Development)

[Translated by James Balowski.]